Michael Dell has always been a man of big ideas. 32 years ago he founded a scrappy business in his dorm room at the University of Texas selling personal computers to students. After quickly dropping out of college he built his company into the world’s biggest PC seller, eventually overtaking the Compaq and forcing the computer giant into merging with Hewlett Packard.

In 2013, amid a soul-searching decline in the PC market, he engineered a $25bn (£20bn) buyout of the company, taking it private in an attempt to steady the ship. And a month ago, he completed the biggest takeover in technology history, a $58.1bn merger with IT giant EMC that took almost a year to go through.

Dell Technologies – to give the company its new name now that it has joined with EMC – is now the world’s biggest private technology company, and with a net worth of $20bn, Mr Dell, 51, is listed by Forbes as the world’s 35th-richest person on the planet. “I just do what I think is right and it’s been working for me so far,” he grins.

At least to the consumer, Dell is best known as the computer maker whose low prices and colourful laptops came to prominence in the 1990s. But the world has changed since then. The PC market peaked in 2011, as the smartphone and tablet took over, and has shrunk by almost a third since then. As this reality became clear in 2012, Dell’s shares fell 32pc, and Mr Dell decided that the only way to turn his company round was out of the public glare.

“It’s so much better, so much easier being a private company,” he says, three years after he teamed up with private equity partner Silver Lake to take Dell off the stock market. “By reframing the business with a longer term horizon, it’s allowed us to make investments, and the results have been very good. We said we’re not going to optimise the business for a 90-day window.”

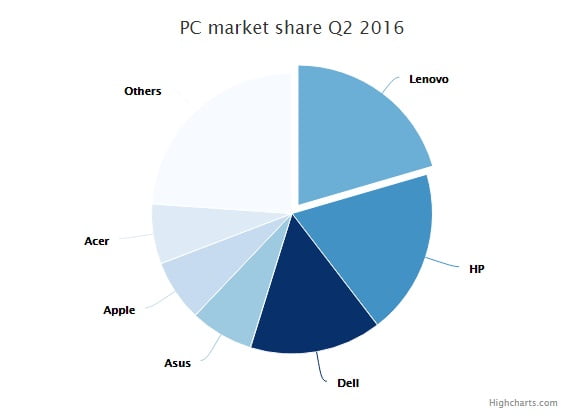

Dell is still a big player in PCs: it is third in the market behind Lenovo and Hewlett Packard, with its share having grown for 15 consecutive quarters, as its chief executive is keen to point out even if that market is shrinking, and personal computers still accounted for most of Dell’s revenues before it merged with EMC.

But the takeover also signified a new emphasis on other areas of the business: enterprise software, servers, cloud computing and security. The new company aims to be a comprehensive shop for selling IT to businesses, a market that is consolidating and changing rapidly as corporate customers rapidly shift their tech resources from software and servers located within offices to the cloud – rented infrastructure at gigantic data centres connected to staff via high-speed internet connections.

“The ability to change business with information has never been greater,” Mr Dell says. “But on the other hand there are economic challenges of various forms and [companies] need to modernise their infrastructure and the way they do IT.

“With that backdrop we saw a tremendous opportunity to create a special company with the combination of Dell and EMC. In the combination you have very little overlap, and you create a business that has the number one position and is leading in a very wide set of capabilities.”

EMC had been in Mr Dell’s crosshairs for years. The companies had worked closely since 2001 and were close to a merger in 2009 before a deal was scuppered by the fallout from the financial crisis.

In private hands, he was finally able to pursue a deal which required Silver Lake to raise $40bn in debt. The takeover was also made extraordinarily complex by the hotchpotch of companies under the EMC umbrella, including 80pc of the publicly-listed virtual desktop software company VMware. Its original price was $67bn, but was ultimately lower because it tracked the value of VMware shares. Combined, the company has annual revenues of around $74bn and 140,000 staff, some of whom may be worried about their positions if, as with almost all big mergers, job cuts are on the table.

Mr Dell says there will be inevitable losses but they will be limited. “[We] dont have a lot of overlap. It’s not one of these conversations where you have tons of businesses that are exactly the same and you’re having a shootout to see who’s going to be in charge. It’s a different kind of combination.”

He does not expand on reports saying that 2,000 to 3,000 positions are at risk, except to say that the losses are “not [significant] really, not in the context of the size of the company”.

Of course, as a private company, Mr Dell is under no obligation to reveal this, and he remains scathing about the short-termism of the financial markets, as other technology companies such as Twitter struggle in the public spotlight. One also suspects that Dell’s Texas base shields it a little from the turbulence of Silicon Valley.

“It’s a bit of a sad commentary on the financial markets that public companies have a difficult time doing things that would be in their best interest over the medium and long term you know," he says. "It says that maybe there’s too much focus on the short term.”

His language suggests there is little rush to return to the stock market, although pundits have speculated that once the dust has settled on its merger, Dell could come roaring back. “We don’t have any plans to go public,” is all its chief executive has to say on the matter.

Regardless, he is clearly enjoying life out of the market’s gaze and believes Dell has prospered. Sales of servers surpassed those of Dell’s great rival HP Enterprise earlier this year, and those of PCs are still growing despite a shrinking overall market.

Computers are still a fundamental part of the company, says Mr Dell, who dismisses the suggestion that he could split off the business as HP did last year when it separated its consumer business, which makes computers and printers, from its enterprise division.

“Just because another company did something doesn’t mean its the right thing to do, and it kind of goes without saying that I’ve never been a guy to do what other people are doing; I just do what I think is right,” he says.

“If you look at the PC, when the smartphone was zooming ahead people said ‘The PC's finished.’ We said the PC may not grow, but it’s going to consolidate.”

He is relaxed about the effect of Brexit, and says that any economic turbulence is often an opportunity for companies like his if customers restructure. “Our business is one that provides productivity, and is the fulcrum and lever for change in progress in these companies and industries. If they don’t avail themselves of that its very dangerous for them.

“We continue to support them and we’re here and we’ll be here following them all round the world, and we’re not leaving.”

Source: http://www.telegraph.co.uk/technology/2016/10/09/i-just-do-what-i-think-is-right-its-been-working-so-far-michael/